“Those things you learn without joy, you will forget easily.”

So the saying goes in Finland, a country with one of the highest ranking education systems in the world. Finland has consistently ranked near or at the top of the PISA survey (which compares 15 year-olds from different countries in reading, math and science) alongside several East Asian countries.

There’s something that makes Finland stand out. What is it?

Well, for starters, Finnish schools assign less homework, do not administer standardized tests, and, perhaps most importantly, engage children in creative play.

Any guess when they begin teaching reading in Finland? According to Anni-Kaisa Osei Ntiamoah, a Finnish kindergarten teacher, “Finnish kindergarten teachers are free to teach reading if they determine a child is willing and interested to learn.”

Willing and interested.

Does individualizing the timing of reading instruction really work? Does student engagement actually matter? The answer is yes. Absolutely, yes.

Why Engaged Learning?

Neuroscientific research about engaged learning reminds us that our brains search for meaning and that emotions drive our brains in learning. According to VanDeWeghe (2009) “what is meaningless is quickly neurologically pruned.” Have you ever crammed facts in your brain the night before an exam? Do you remember this information now? Probably not. That’s because meaningful connections weren’t made. See? Even our biology shows that engaged learning really matters.

Experts claim that the best way to store information into long-term memory is by processing it through multiple memory pathways.

Which memory pathways exactly?

- Semantic – learning through auditory and printed language such as a classroom lecture.

- Episodic – learning in the context of physical locations, events and lived or imagined experiences such as films and narratives.

- Procedural – learning through hands-on, kinesthetic experiences such as lab experiments.

- Emotional – taking in information through an emotional experience

- Spatial – learning through visual and graphic representations of learning materials such as maps or diagrams.

Can we really teach in a way that allows students to take in the information through multiple memory pathways simultaneously?

Yes. This is why I am personally so excited to create lessons and resources based in experiential learning.

What is Experiential Learning?

According to Felicia (2011), experiential learning can be defined as learning through the reflection on doing.

The classic example that comes to mind is learning to ride a bike (which we never forget, right?) This kind of learning involves taking in information through multiple memory pathways and involves a good deal of reflection in order to be successful.

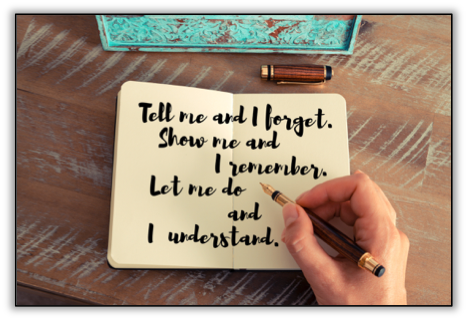

Perhaps Confucius articulated it best:

Is there room for more Experiential Learning in our Classrooms?

Researchers from the University of Virginia noted a decline in playful learning opportunities in American kindergarten classrooms between 1998-2010. Specifically, they noted a decrease in the use of child-selected activities (such as stations) and enrichment including music and art with an increase in the use of textbooks, worksheets, assessments and teacher-led instruction.

How does Experiential Learning Pertain to Speech-Language Therapy?

As SLPs, our ultimate goal is for our students to generalize the skills that we’re teaching them in our formal, clinical setting to natural, everyday situations. Research shows that generalization is considered a major clinical challenge among speech-language pathologists. However, there are many ways we can integrate experiential learning principles into our therapy so that the learning targets we’re teaching become more motivating, meaningful and, therefore, memorable for our students. We want our students to apply what we’re teaching, to reflect on it and store the information in their long-term memory. Experiential learning can make this happen.

What can we do?

- Teach in the context of a memorable experience. This can be as simple as creating an interactive story with articulation cards or practicing language skills during “Show and Tell” (as opposed using drill or drill-play techniques).

- Set aside a time and a place for this type of learning. Although some prep time is required initially, oftentimes experiential learning lessons can last over the course of several sessions and are meaningful for many students on your caseload.

- Attend a field trip. If several of your students are going on a field trip, try to tag along if it’s logistically possible. You’ll be pleasantly surprised by the vast array of meaningful applications for the speech and language skills you’re targeting with your students.

- Take photos of experiences to review and reflect on later. You can even take photos of your students in specials classes like physical education or art. Review directions, prepositions, sequences, vocabulary and social situations.

- Regularly incorporate evidence-based, child-centered therapy approaches, which work well in the context of experiential learning lessons:

- Focused stimulation

- Indirect language stimulation

- Vertical structuring

- Milieu teaching

- Script therapy

- Play! As SLPs, we all know the power of play. Am I right?

I’ve created over 40 detailed and easy-to-implement experiential learning lessons that are available to anyone who needs ASHA CEU’s.

My online course with Northern Speech Services covers the research basis for these interventions and does all of the planning for you! It has received top peer reviews and I’m really proud of all it has to offer! (And, yes, I do briefly mention Finland in the course!)

Do you enjoy teaching in the context of a meaningful experience? If so, I’d love to hear about it!

References

Caine, R.N., & Caine, G. (1994). Making connections: Teaching and the human brain. Alexandria, VA. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Caine, R.N., & Caine, G. (1997). Education on the edge of possibility. Alexandria, VA. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Chapman, J.E., Herbert, E., Avery, C., & Selmar, J. (1961). Clinical practice: Remedial procedures. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, Monograph Suppl. 8, 58-

D’Orio, W. (n.d.). Finland is #1! Retrieved March 01, 2017, from http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=3749880

Felicia, P. (2011). Handbook of research on improving learning and motivation through educational games: multidisciplinary approaches. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Gray, S. & Shelton, R. (1992). Self-monitoring effects of articulation carryover in school-age children. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 23, 334-342.

Jensen, E. (1998). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria, VA. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Lyons, C. (2003). Teaching struggling readers: How to used brain-based research to maximize learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Partanen, A. (2011, December 29). What Americans Keep Ignoring About Finland’s School Success. Retrieved March 01, 2017, from https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/12/what-americans-keep-ignoring-about-finlands-school-success/250564/

Paul, R. (2001). Language disorders from infancy through adolescence: assessment & intervention. St. Louis: Mosby.

Pert, C. (1997). Molecules of emotion. New York: Scribner’s.

Sommers, R.K., The therapy program. In R. Van Hattum (Ed.), Clinical Speech in the

Schools. Springfield, Ill.: Charles C Thomas (1969).

Sylvester, R. (1995). A celebration of neurons: An educator’s guide to the human brain. Alexandria, VA. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

VanDeWeghe, R. (2009). Engaged learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Walker, T. D. (2015, October 1). The Joyful, Illiterate Kindergartners of Finland. The Atlantic. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/10/the-joyful-illiterate-kindergartners-of–finland/408325/

Wolfe, P., & Brandt, R. (1998). What do we know from brain research? Educational Leadership, 56(3), 8-13.